Most of the artwork in this exhibition was first exhibited at the Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art, Momentum, that was held for the eighth time in 2015. The curators – Jonatan Habib Engqvist, Birta Guðjónsdóttir, Stefanie Hessler and Toke Lykkeberg – selected the theme of „Tunnel Vision“ for the exhibition. They wanted to explore how individuals and groups isolate themselves on the basis of certain firmly held beliefs or preferences, despite our having supposedly entered an age where verifiable information is freely available through the Internet. This is an odd contradiction that seems to characterise our time: We live in an era of incredible technical and scientific progress, of clear and logical thinking, and yet many of us seem to seek out murky cultural nooks where we can nurture our heretical eccentricities in the company of a few, likeminded people. This is a world that Steingrímur Eyfjörð has chosen to explore in many of his exhibitions.

His subject is what he calls contemporary folk tales, all sorts of ideas, narratives and conspiracy theories that form a remarkably important part of our world view, even if they do not conform to the ideas of scientists or logicians. This is a vast field and crowded with contradictory material: Ghosts and aliens; ancient wisdom; conspiracy theories about governments, secret societies or multinational companies; unconventional scientific or medical theories and home remedies for every problem or complaint. Such ideas permeate all human culture and they are at once mysterious and perfectly obvious. They are the subject of innumerable books and radio shows, and the Internet is half-full of sites offering such narratives and explanations. Even with this exposure, they are difficult to pin down; the arguments seem to evade close examination. But though they may not stand up to rigorous scientific scrutiny – and sometimes defy common sense – they are, despite everything, evidence of our unending search for knowledge and our attempts to understand the world we live in. Our world certainly contains a lot of mysterious things, things that science often does not seem to address or explain, but that we find difficult to dismiss altogether. In order to explain the unexplainable, the strange and extensive field of folk tales has developed and grown. It reaches all the way back to pre-historical times but renews itself in every era and seems to thrive just as well under the glare of electric lights as it did in the murk of the ancient world. The issue is further complicated by the fact that much of it contains a kernel of truth or preserves knowledge that could well be of use to us today: Many old home remedies actually cure us, ancient spiritual theories can help us see beyond our stressful everyday lives and old narratives can help us to better understand ourselves and our world.

The search for knowledge and the role of narratives in this search have long been Steingrímur Eyfjörð’s primary concern. In this exploration he discovers the intersection of creativity and experience. Despite all our logic and enlightenment, narratives are still our primary tool for organising and understanding our surroundings and our experience. This is the foundation of our myths and folk tales, and though science and philosophy pretend to have pushed them all aside, that is only true on the surface. Narratives are easier to follow than scientific theories and, in terms of everyday experience, they carry a higher explanatory capacity – so long as we believe them. A good novel or film can teach us more about life than a shelf of academic books and so much in life does not seem to be addressed at all by the generalisations of science: Mysterious events and coincidences, inexplicable connections and remedies that work, however hard the doctors may shake their heads.

In this exhibition, as often before, Steingrímur offers up incongruous fragments, a collection of ideas and images that never quite manage to form a unified whole, even when they all seem in some strange way connected. As we move from one work to the next, the explanation always seems to be just around the corner: The narrative that will complete the picture and make the connections in this disturbing multiplicity. This is the core of the folk tale as Steingrímur presents it to us. It is like the world of stories that Scheherazade weaves in the Arabian Nights, unending and all-encompassing. If something seems unclear, another story can always be told about it. One narrative explains the other and soon the web of stories has become so complex that we get lost in it but keep thinking that somewhere in the tangle we can glimpse all answers, somewhere in there is the answer to every question, the hand that directs the heavens, the destiny we must grasp or the king who rules the world behind the scenes.

In the 2001 exhibition “Projection”, Steingrímur explored this search for knowledge through one mysterious case. His friend had found a hidden space in her kitchen wall and, in it, a woman’s slip and underclothes. The clothes were torn and they seemed to have been hidden away in the wall for decades, which prompted curiosity about the story of what had happened. Who was this woman? Why were her underclothes torn and why had they been hidden away in a wall? In search of answers, Steingrímur contacted four mediums and wrote down their attempts to clear up the story. It seemed as though something terrible might have taken place though it was hard to discern the details. To get closer to the story, Steingrímur even put on the underclothes and surrounded himself with objects that the mediums thought might be connected to the event. In the exhibition we could read the words of the mediums, see photographs of Steingrímur wearing the slip and examine the underclothes in a glass case.

“Projection” is primarily a record of the creation of the exhibition itself and yet there is a real event and a mystery in the background. A mystery that we seem to have no way of understanding. Something happened and there is a story there that we cannot unravel. The world is full of such mysteries but it is difficult to accept that we will never be able to solve them. Most of us find it almost unbearable that our narratives have so many holes in them. Everything must be connected in some way and all the fragments must somehow fit together, if only we could see the pattern. This feeling is at the root of our quest for knowledge but it is also why so many of us are attracted to mysticism and esoteric science – there, at least, we do not have to accept the unacceptable.

Steingrímur approaches all this with an open and sympathetic mind. His working method in many ways mirrors the subject. He pursues these ideas, symbols and narratives without prejudice and his artworks make connections in an attempt to trace the story that we know will have no conclusion. The artworks also show how interesting and enchanting Steingrímur finds this world of folk tales. One of the clearest examples of this came in the form of a small sheep pen that he exhibited in Venice when he was selected to represent Iceland at the Biennale in 2007. The audience saw the sheep pen with a bucket of water and small mound of hay but on the wall we could also read the story of how the work came to be made. Steingrímur’s Venice exhibition explored the various interconnections of folk tales and national identity in Iceland, including trolls, the symbols of nationalism and the peculiarly Icelandic tradition claiming that the migratory golden plover bring spring to the island. Steingrímur had the idea of underscoring the Icelandic belief in elves by bringing an elfish sheep to the exhibition. He contacted a medium who speaks to elves and asked him to broker a contract for the purchase of a sheep. The elves explained in detail how the pen should be constructed and how the sheep should be provisioned and cared for. When the price, a whetting stone, had been paid, the sheep was delivered to the pen. This story has all the hallmarks of a traditional elf tale. The communication seems to be a perfectly normal livestock purchase, such as are negotiated every day on farms everywhere, except in the detail that one of the negotiating parties is an elf. By going through the whole process – negotiating with the elves, building the pen and transporting it to Venice – Steingrímur lends the story a certain credence. It is then up to the viewer to experience and interpret the artwork, standing before the empty sheep pen and reading the story that tells us there is an elfish sheep in it. Many, of course, simply shook their heads at such nonsense and some elected to treat the whole thing as a kind of sophisticated joke. Yet the work was also an occasion for reflection on stories and folk beliefs, and on how fragile our own belief is in the explanatory capacity of narratives. One could say that the work existed primarily in the mind of the viewer who had to decide how to approach it and then stand by his or her decision.

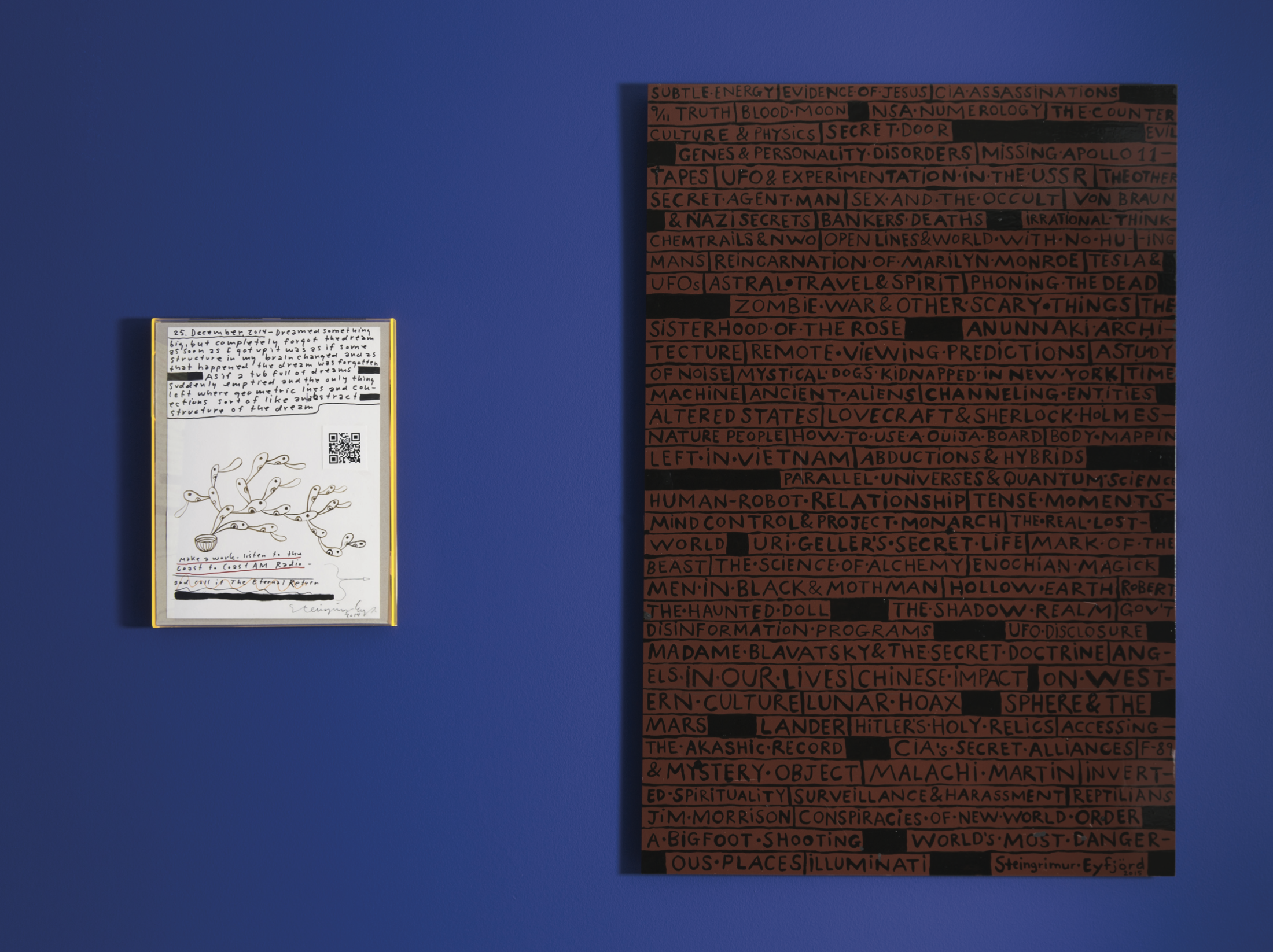

Steingrímur’s exhibitions are usually full of texts and many of the artworks are primarily composed of handwritten texts, sometimes accompanied by images or drawings. This presentation has its background in the artistic environment that he was part of in the 1970s in Iceland, around the gallery and collective known as Suðurgata 7, which was heavily influenced by the Fluxus movement. He later completed his studies in the Netherlands where similar influences prevailed. But his use of text also brings together the many treads of his complex and highly individual working method. The artworks become documents of their own creation, reflecting the methods that Steingrímur has used to come to the result that we see in the exhibition. They document a journey where he has delved deep into his subject in order to understand it. This journey is subject to certain rules and the artworks also often involve rules – explicit or implicit – that the viewer has to follow. We are given instructions that allow us to discover the subject for ourselves or add our voice to the narrative. Steingrímur has even harnessed the Internet to this exploration by including QR codes in some of the pieces that we can read with a smart phone to find web sites where we can continue the quest.

Audience participation is very important in Steingrímur’s art and many of his projects also involve some kind of conversation or collaboration. In one example, he has people look at drawings and then records their comments directly on the drawing. Other works are records of conversations. In one of the projects he is currently working on, he collaborates with other artists, literary theorists and others to explore the location of Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain. All this is part of the creative process, like a never-ending conversation or journey.

Another collaborative project has been ongoing for a few years. This is the Ley Line Project which Steingrímur heads with the Swedish artist Ulrika Sparre. They first introduced their theme in an exhibition at the Reykjavík Art Museum in 2012. In 2015 a book on the project was published in Sweden and more events and exhibitions are planned. In collaboration with others, Steingrímur and Sparre have explored old ideas about the ley lines, lines of energy in the ground. This is an area where science intersects with mysticism and ancient traditions, as there is much evidence that ancient peoples were aware of these lines and aligned their settlements and lives with them. The study of ley lines involves different modes of approach, research methods and narratives, that can be difficult to reconcile but that are all part of our overarching search for knowledge and understanding. By exploring them within the context of art, Steingrímur and Sparre can pull the different threads together without the prejudice of a pre-given set of ideas. They can bring people from different fields together and turn the museum into a laboratory where the audience can enjoy the artwork, study and take part in experiments. This is very much the working method that Steingrímur has sought to develop in all his art.

The exhibition in Gallery GAMMA should thus be seen as part of a larger, long-running project where Steingrímur explores the margins of humanity’s quest for knowledge. The goal is not merely to discover something unusual and odd but to understand how we comprehend the world and how our narratives function in our attempts at making sense.